At the TIPS community building event in Preston in December 2017, we lead a workshop exploring the temporalities of consent by mapping out the relationships between different services and products a user may consent to over time. We investigated the potential relationships and connections between different services and how they might be influenced over time. This design workshop considered the life cycle and temporality of consent beyond the on-the-spot instance of a user agreement. This aimed to further understanding of how internal and external factors may affect user consent over time and throughout different aspects of user’s lives. Questions around how consent may be influenced by a user’s life circumstances as well as technological developments and legal requirements were creatively explored via a set of design cards and activities.

This workshop aimed to consider how more temporal or situation-specific forms of agreements may allow for more dynamically designed consent models. Moreover, the design activities aimed to expose and debate the relationships between different services, data and how they may develop over time. Changes in life circumstances may shift the way we view consent and what data we share. However, existing models of consent do not take this into account and services often do not allow a user to delete their account or the data that has been collected about them. So, what challenges for consent arise from changing circumstances in life and what are the relationships within such complex networks of shared data?

Workshop Overview:

The workshop was divided into three sections to (a) set up the participants’ context, (b) map temporal connections of consent and (c) investigate how potential changes in circumstance may impact users’ perception and understanding of consent over time.

- Starting from someone else’s perspective:

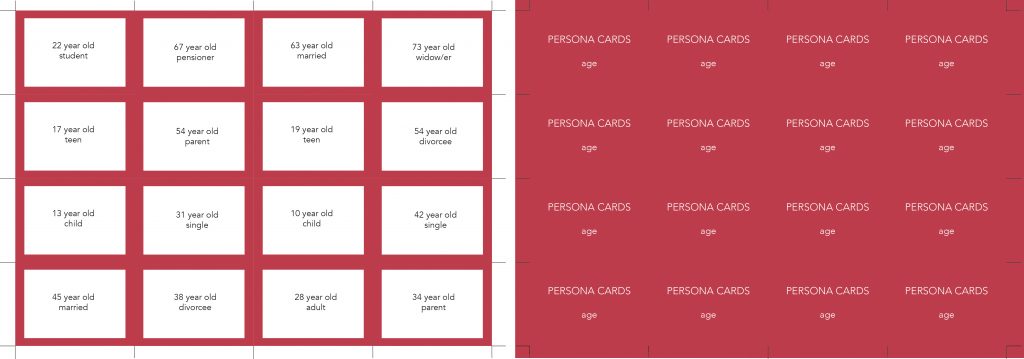

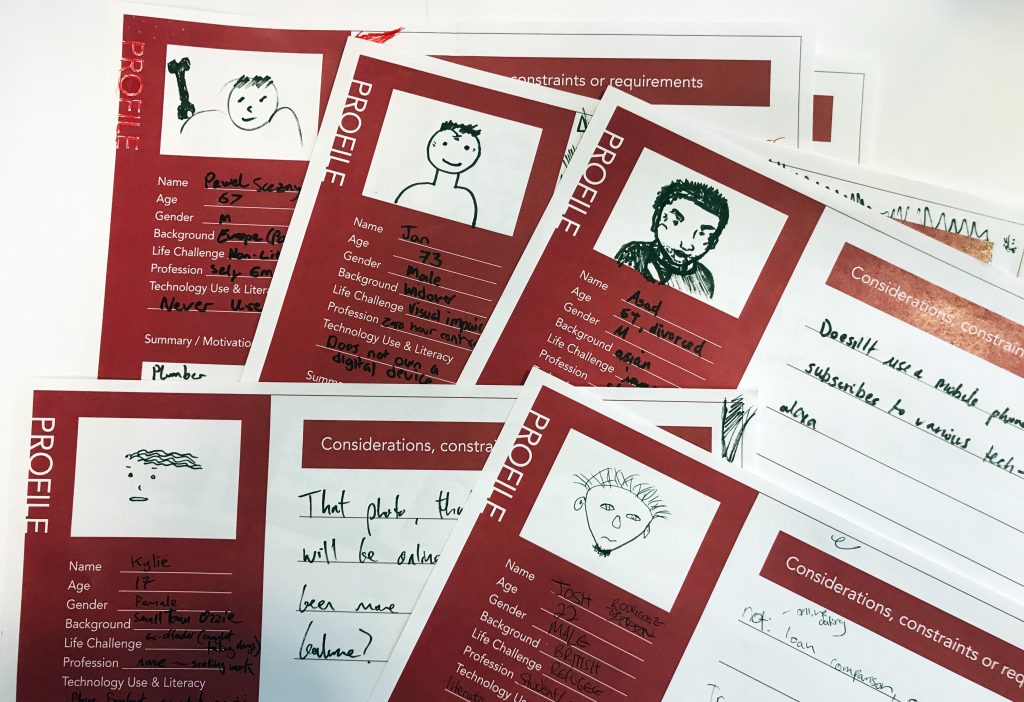

The initial exercise aimed to create a persona for each workshop participant. Predicting a fairly homogenous participant group of early career HCI researchers, we developed a set of Persona Cards that would allow participants to create a unique profile different to themselves to think through during the workshop. Similar to other Persona creation tools, we gave participants 6 aspects that together generated a relatively randomised persona. These Persona Cards included age, gender, cultural background, work situation, technology literacy and life challenges. The life challenge cards covered varying aspects of a person’s live ranging from impoverished background, varying disabilities to health issues and criminal offences. This aimed to move participants away from a perspective of norms and ‘normality’ to highlight people’s differences and unique lives. From the randomly selected cards, we asked participants to imagine their persona and draw out a Persona Profile describing their background, life and motivations.

Participants not only filled in their persona profiles but created very detailed backstories for their persona, giving them names, issues they may be struggling with and reasons for current situations. This allowed participants to create and think through consent from someone else’s perspective. Although there may always be slight preconceptions or unavoidable stereotype influences, the personas gave participants another viewpoint beyond their own. During the rest of the workshop, participants often switched between their own perspectives or personal experience on some of the topics back to how their persona may potentially be impacted, react to or deal with a given issue of consent and agreement.

- Creating a temporal consent map

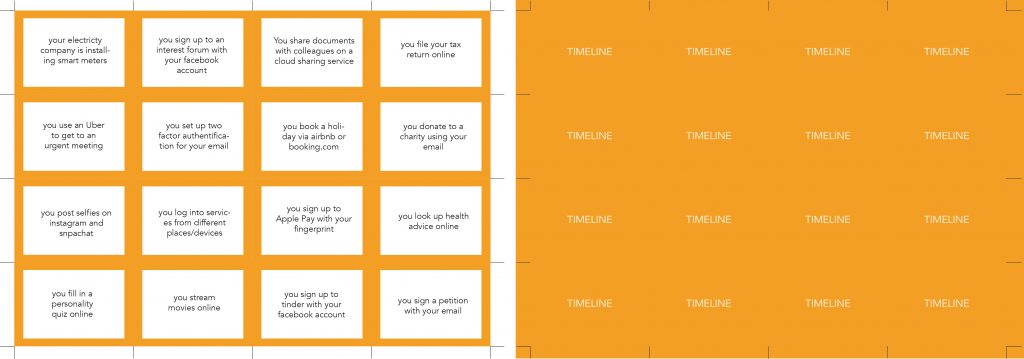

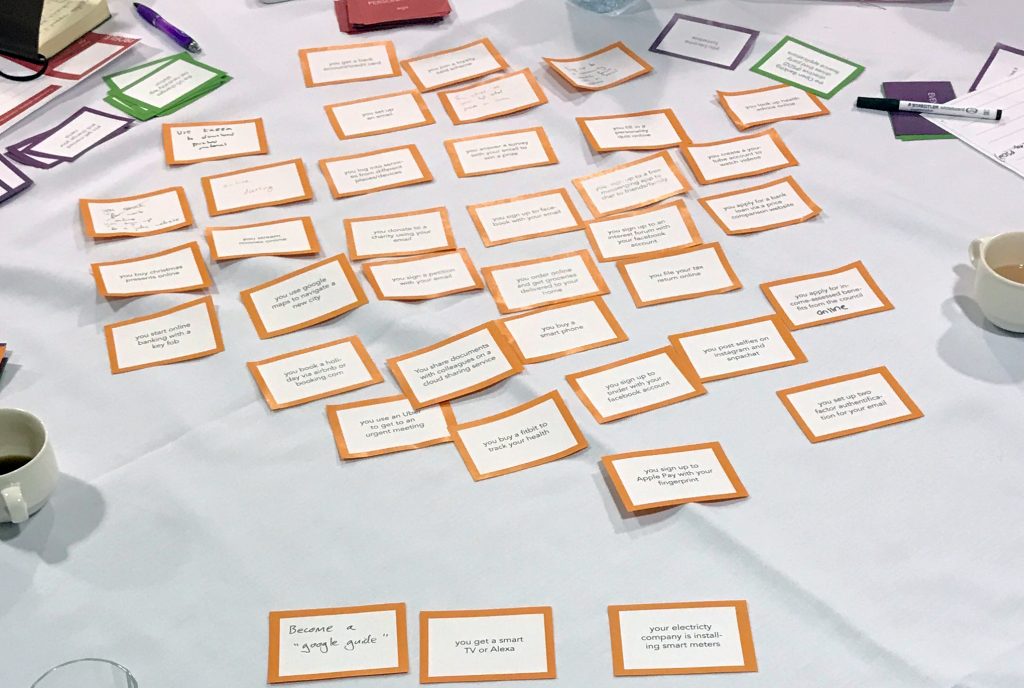

The second set of cards (Consent Event Cards) we created were aimed to cover a series of consent instances that some or many users are currently using, have used in the past or may use in the future. These included a series of devices, such as laptops, public screens, smart phones, watches and interactive things. Different uses of services and products were covered from email, social media, grocery shopping, smart homes, banking, traveling, TV subscriptions and online dating. The aim of this exercise was to map out the entire set of Consent Event Cards and debate their relationships between one another. What services may be based on data or information from another service and how do they influence each other and the user? This activity mapped out a relatively chronological and relational network of services and how they relate to each other. For example, it is required to sign up to and own an email account (often done years prior) to create a Facebook account which is in turn required to register and validate an AirBnB account.

Obviously, there is not only one clear chronological relationship between these services but there are particular steps and patterns that are similar in order, i.e. email sign ups come first. Additionally, the discussion of personal data and types of personal data brought into focus the different layers of identities and what those layers may be. The intertwined relationship between personal and professional identities, between offline and online identities which were debated. But the difference in perception of sharing these varying identities ranged as well. Bank account data is kept much more secure than an email. And digital identities can be created in multiple forms (anonymous or identifiable) while biometric data is problematic crossing these boundaries. Although many of our identities or data layers of our identities are increasingly enmeshed this does not however allow users to easily transfer data between services or their service silo.

- Debating technological changes and life challenges

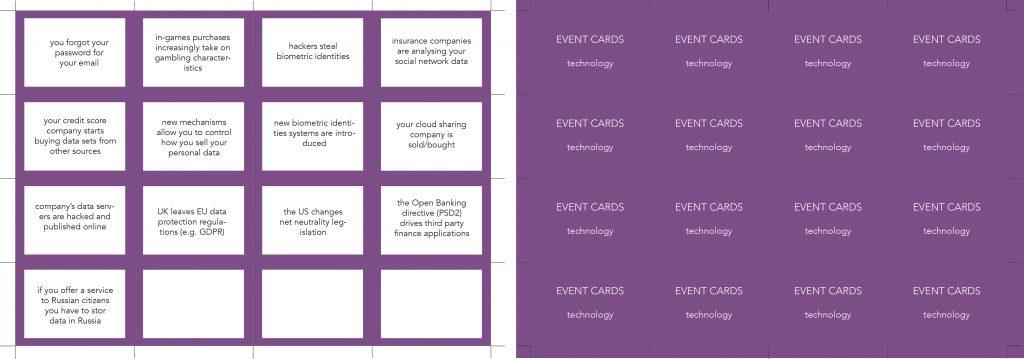

The last activity in the workshop then included the third set of cards which consisted of events that aimed to change the circumstances of or for the personas in relation to both shifting technological development as well as user’s changes in life circumstances which may influence a user’s perspective and understanding of consent and how/where their data is shared. The Life Event Cards included events such as getting married/divorced, having a child, moving countries, being accused of harassment, becoming ill, jobless or homeless. The Technology Event Cards covered areas of user password issues, occurring company’s security breaches, data being leaked or hacked, geo-political developments (e.g. Brexit) or new data legislation (e.g. GDPR/PSD2).

Through the personas, we discussed accessibility concerns, data longevity, transitions and reliance on others in relation to consent for more vulnerable users who may not have a permanent home, may not realise the impact of their digital actions on their futures or may not be able to access services by themselves. Going beyond the practice of children helping their parents with technology and consent, this raised questions of what consent may mean when it is mediated through a third party and what it may be like to have personal assistance with digital services (e.g. due to physical impairments). How should assisted models of digital consent be reframed or what should guidelines for assisted consent entail? More generally, this lead to considerations of ways to allow users to reconsent or deconsent to services more easily. Or that the moment of consent could be extended or repeated not only when Terms of Service change for the business but when a user’s perspective of a service may change due to new circumstances. How would such a user-centered consent model be designed and what triggers or actions may be designed into it? When signing up to consent, could the service ask how or when you would like to review your consent in the future with potential options, such as would you like to review your consent (a) after 7 days, (b) when you get married, (c) when you look for a job?

Life transitions were also generally contemplated. Moving from university lifestyle (and digital lives) to emerging concerns over publicly available data for potential employers and future impressions of one’s self. In particular, often younger (and increasingly younger) users may be unaware of the influence that the openly shared personal data may have on their future lives. In particular in relation to potential criminal or other offences committed during rebellious teenage years which may haunt one’s digital life years later. How could services be designed to offer more security for younger audiences beyond explicit rights to be forgotten requests to specific companies? Could businesses implement life phases that allow users to ring fence or wall off different stages of their life, e.g. before graduation? Could data automatically expire or be siloed when turning 18, i.e. the user can decide to start fresh and set up an “under 18 ring fence”? Or could a user change/hide whole threads or aspects of their digital lives based on different events to create different narratives or digital selves? This may not only apply to younger audiences but also for people who might want to change their use of a service based on a life event, such as having children, getting divorced, moving abroad. Generally speaking, what is the expiration date of data? Is data infinitely used and reusable? Who is control of these decisions and who controls what is ‘forgotten’ and when? How does the human memory compare to data memory? What are human’s mechanisms for remembering but also for forgetting?

In summary:

Upon reflection, the perspectives and opinions expressed during this workshop about a map or timeline of consent was based on a fairly homogenous group of HCI researchers of similar age, generation and not overly divers backgrounds. We considered how our experiences of growing up with technologies (now being in our 20s/30s) may have influenced the relationships of consent that we drew and how this may differ from the upcoming generation of the so-called digital natives. Will they still sign up to an email first or do they start with a phone number and a snapchat account? At what age will they agree to their first Terms of Service to use a device, product or service?